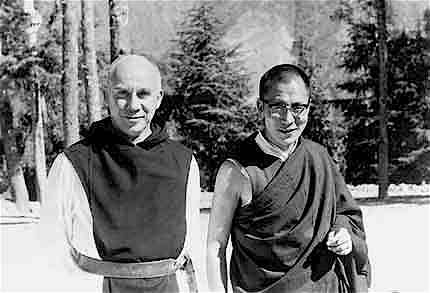

Thomas Merton has become an icon to modern spiritual seekers. He courageously dialogued with monks of other faiths and discoursed with them on being a monk and the pursuit of the spiritual life. He met Dalai Lama in Dharamsala and had several memorable conversations.

November 8, 1968,

Dalai Lama asked Thomas Merton a lot of questions about Western monastic life,

particularly the vows, the rule of silence, the ascetic way, etc.

But what concerned him most was:

Thomas Merton has become an icon to modern spiritual seekers. He courageously dialogued with monks of other faiths and discoursed with them on being a monk and the pursuit of the spiritual life. He met Dalai Lama in Dharamsala and had several memorable conversations.

November 8, 1968,

Dalai Lama asked Thomas Merton a lot of questions about Western monastic life,

particularly the vows, the rule of silence, the ascetic way, etc.

But what concerned him most was:

Did the "vows" have any connection with a spiritual transmission or initiation?

Having made vows, did the monks continue to progress along a spiritual way, toward an eventual illumination, and what were the degrees of that progress? And supposing a monk died without having attained to perfect illumination? What ascetic methods were used to help purify the mind of passions?

He was interested in the mystical life, rather than in external observance.

And some incidental questions: What were the motives for the monks not eating meat? Did they drink alcoholic beverages? Did they have movies?

Thomas Merton's early life is well known from The Seven Storey Mountain. He was born in 1915 in the French village of Prades. His father, Owen Merton, was a painter and-when financial need demanded-a part-time musician who had left his native New Zealand seeking a wider world. His mother, Ruth, was an American of Quaker background with artistic ambitions. They met in Paris as art students and were working in the south of France when Thomas was born.

Artistic parents are usually both a blessing and a curse, and the Mertons were no exception. Thomas inherited gifts of insight that frequently outran even his considerable talents as a writer.

Thomas Merton's early life is well known from The Seven Storey Mountain. He was born in 1915 in the French village of Prades. His father, Owen Merton, was a painter and-when financial need demanded-a part-time musician who had left his native New Zealand seeking a wider world. His mother, Ruth, was an American of Quaker background with artistic ambitions. They met in Paris as art students and were working in the south of France when Thomas was born.

Artistic parents are usually both a blessing and a curse, and the Mertons were no exception. Thomas inherited gifts of insight that frequently outran even his considerable talents as a writer.

The mid-1960s brought him to the brink of disaster. Merton had a back problem requiring an operation at a Catholic hospital in Louisville. When he recovered from the anesthesia, he was anxious that he had missed daily communion. He began making notes on Meister Eckhart. His long- desired hermitage awaited him back at Gethsemani. To the eye, it was business as usual.

But a pretty young student nurse (Margie Smith) came in 1966 at St. Joseph's Hospital in Louisville. A Catholic, she knew of Merton from a book her father had given her. Something erupted between them- even though she had a fiance in Chicago. On leaving the hospital, he wrote her about needing friendship. She wrote back, instructed by him to mark the envelope "conscience matter" (lest the superiors read the correspondence). Under "conscience matter," Merton sent a declaration of love. Thus began a series of deceptions, and Merton only narrowly avoided the shipwreck of his monastic vows because of the impossibility of the whole situation.

Merton used friends to carry messages and provide meeting places. He ignored warnings and even thought of a chaste marriage (though chastity was not particularly high in his thought at that point). They met for dinner and drinks, wine and picnics, listened to music together. Merton wondered how he could live without her.

Dom James found out about the relationship (another monk overheard a telephone conversation), and ordered Merton not to contact the young woman again, but surreptitious contacts went on for some months.

Some of the available notes are striking: "Passing near the hospital, I thought I was slowly being torn in half. Then several times while I was reciting the office, felt silent cries come slowly tearing and rending their way up out of the very ground of my being." Though he was wrong, it is hard to wholly condemn him. The atmosphere of the 1960s drove other people into much worse, and in the end he did the right thing. The relationship between Merton and Margie which some scholars argue was sexual, while others insist it was chaste transformed his life and faith.

Margie Smith went back to Ohio and married a doctor and raised sons. In all these years she has never once spoken publicly of Merton. Even Michael Mott, the authorized biographer, with access to all the Merton papers, with his prodigious research, never met her. (They spoke on the phone.) She has painted, she has taken advanced studies in nursing, she has kept up with the Louisville friends who were close to Merton. She has declined to become part of a culture in America that would reward somebody with millions for writing a book titled "I Was Thomas Merton's Secret Love."

By Robert Royal, The Several-Storied Thomas Merton, February 1, 1997

Trappists: Religion in the Kentucky wilderness, Washington Post, 25 January 1999